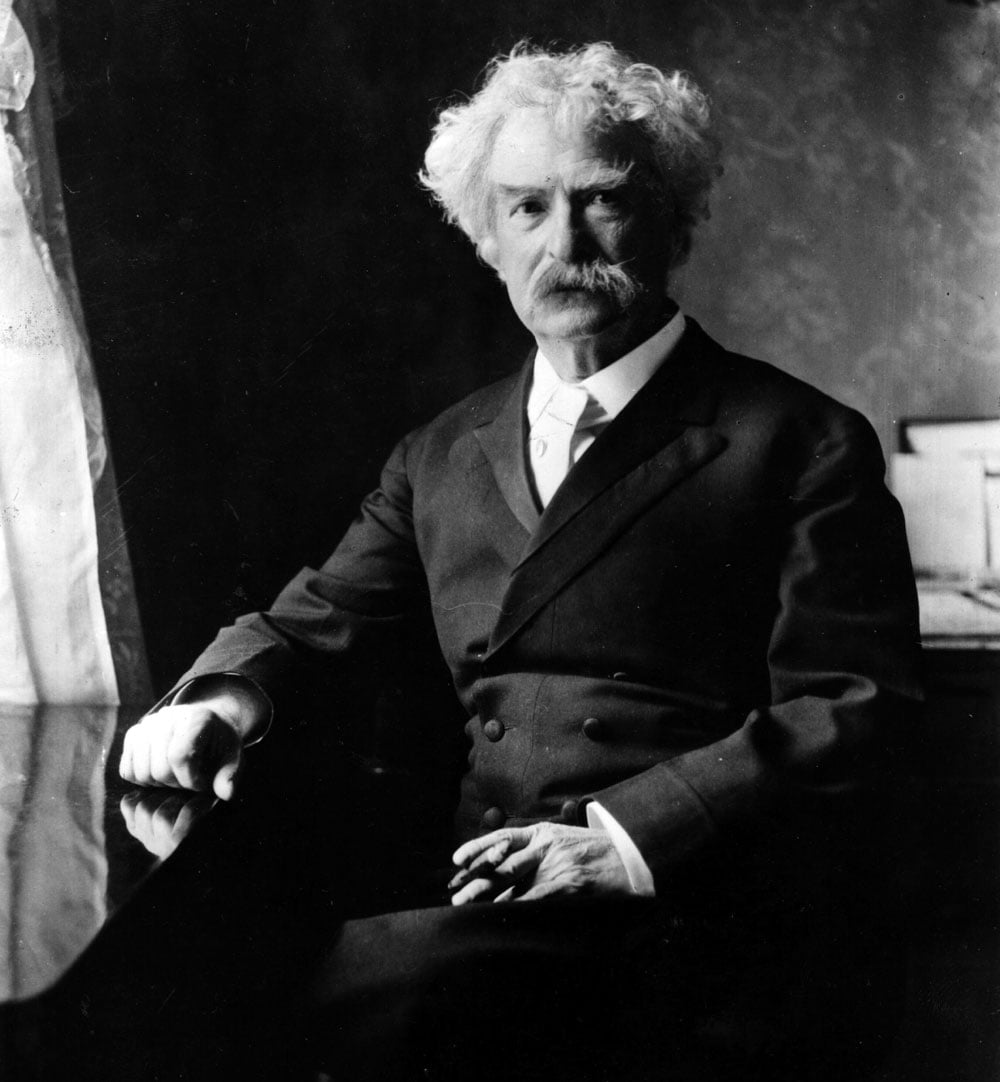

Biography Mark Twain

The name Mark Twain is a pseudonym of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Clemens was an American humorist, journalist, lecturer, and novelist who acquired international fame for his travel narratives, especially The Innocents Abroad (1869), Roughing It (1872), and Life on the Mississippi (1883), and for his adventure stories of boyhood, especially The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885). A gifted raconteur, distinctive humorist, and irascible moralist, he transcended the apparent limitations of his origins to become a popular public figure and one of America’s best and most beloved writers.

Mark Twain’s Works (Top 10)

1. Roughing It (1872) is Twain’s second book, a comedic romp through the Wild West with hilarious sketches of the author’s misadventures. The book recounts Twain’s flight from Hannibal to the silver mines of Nevada at the outset of the Civil War. We read of his encounters with Mormons and Pony Express riders, gunslingers and stagecoach drivers along his way. He eventually finds himself in San Francisco and the California goldfields, where he strikes pay dirt with the mining camp tall tale, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” Twain’s West has been mostly ignored in subsequent popular depictions of the frontier, which concentrate on the bold-faced named outlaws, lawmen, and Indians like Jesse James, Wyatt Earp, and Crazy Horse. This is classic early Twain: rowdy, rambunctious and very funny.

2. The Gilded Age (1873), the novel co-authored by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner that named the era, is a wonderfully sharp satire on American manners and morals, an early guide to political corruption at the highest levels, with loving word-portraits and humorous illustrations depicting the scoundrels and speculators that drive the plot and American politics. It is, among other things, a preview of money’s pervasive influence in 21st-century Washington. There is no small irony in Twain’s depiction of gullible characters involved in get-rich-quick schemes, as his own finances were nearly undone several times by poor investments.

The river novels come next:

3. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and 4. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) represent Twain’s rise to literary prominence and maturation as an artist, displaying his genius for dialogue and dialect, unforgettable characters and prescient social commentary cloaked in the awesome spiritual presence of the Mississippi River (to appreciate fully Twain’s devotion to the river, go on to read Life on the Mississippi (1883)). Twain’s love for the river started as a boy, growing up within sight of the Mississippi, and his affair deepened with his stint, cut short by the Civil War, as a river boat pilot. He saw and recalled all matter of humanity from those formative years and poured all of it into these three volumes.

5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) is an entertaining and engaging celebration of American ingenuity and republicanism, sending salvos across the pond toward the calcified conventions of European nobility and The Established Church. Feudal conventions and institutions and the arrogance of power are blown to smithereens. Twain understood that the Fish Out of Water story (a 19th century man somehow transported to medieval England) was the perfect vehicle for social commentary. Twain loved England, and the people of that nation held him in the highest esteem, in spite of his trenchant criticisms of their history and customs.

6. The Tragedy Of Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins (1894) is even more powerful and compelling, a step beyond Huck Finn’s voyage to enlightenment with the truant slave Jim; Roxy’s tainted blood and terrible decision to switch racially mixed babies shortly after their birth to give her own child a clear path toward success and respectability, Puddn’head’s forensic clarity, the awful juxtaposition of good and evil, black and white, nature versus nurture are explored brilliantly by Twain. “Puddn’head Wilson’s Calendar,” an extended, embedded sampling of Twain’s legendary aphorisms and witty quips is a bonus. Like many of Twain’s later works, Pudd’nhead reflects his darkening personal path.

7. Following the Equator (1897), a global travelogue in the Twain style, declares his war on imperialism at home and abroad. On a lecture tour between 1895 and 1896, Twain travels the world, both to cut into his debt-ridden finances and to generate material for his next book. In Australia, New Zealand, India, and South Africa, he finds oppression, superstition, racial animus, and sheer ignorance. For all his critiques of foreign cultures and customs, he was just as leery, at the dawn of the American century, of our own presumption in exporting our values to “lesser” peoples.

8. The Mysterious Stranger (1916), posthumously published, is a culmination of Twain’s musings on man’s dual nature and the ongoing battle between God and Satan for control over our poor, damned souls. By the end of his incredibly active and productive life, Twain was beaten down by age and loss, concluding that we are but flawed creatures; life is a game of dominoes leading inexorably to the end. Even when the title character observes that “Every man is a suffering-machine and a happiness-machine combined,” working in harmony, you can’t help thinking that the suffering portion of Twain’s own life had triumphed and was slowly drowning out what little joy remained to him.

9. Eve’s Diary (1906), among his last works, don’t miss the illustrated edition of this one, Twain’s heart-felt and emotional tribute to the first woman and his late, lamented wife, Livy. Lester Ralph’s controversial nude drawings of Adam and Eve (which got the book banned in at least one New England public library) beautifully complement the lost innocence encountered in the garden and we are left with a bittersweet, ineffable sense of loss.

10. Autobiography – Finally, Twain’s ultimate masterpiece, a projected three volumes. Issued by the Mark Twain Project beginning in 2010, it presents the author on his own terms, flaws exposed, short attention span acknowledged, brilliance revealed, the final testament of the most openly human and humane writer we have ever known.